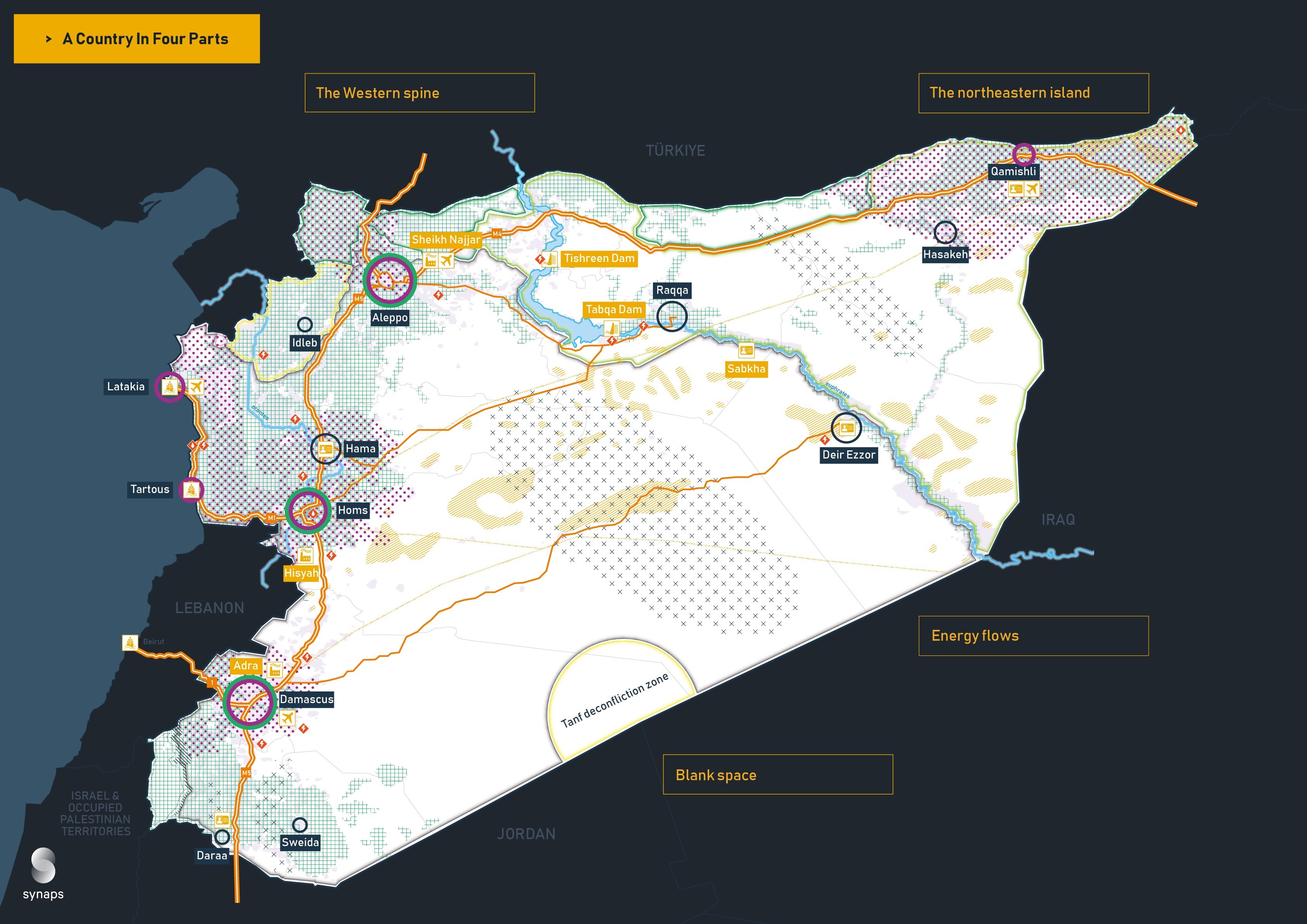

Mapping Syria's social and economic geography

Since 2011, maps of Syria have emphasized fragmentation. That focus is understandable. But it also obscures social, economic, and environmental links that predate the conflict and endured throughout it. Designed in October 2024, this map shows traits that shaped Syria's war, fueled the regime's December collapse, and now shape Syria's transition.

Bird’s-eye view: A diagram in four parts

Even a glance at Syria’s geography reveals factors that organized the country long before 2011, steered the course of the conflict, and will continue to structure the country’s future.

1. The Western spine

Most of Syria’s population, industrial capacity, and transport infrastructure sits on the axis stretching north from Damascus to Aleppo, and west to Latakia and Tartous. Sometimes glibly referred to as “useful Syria,” the region also encompasses some of the country’s best farmland. Control over the M5 highway was a core strategic objective in Syria’s war, from early clashes to the opposition’s lightning offensive in December 2024.

2. The northeastern island

Historically, the region northeast of the Euphrates River and southwest of the Tigris was known as al-Jazeera: a fertile “island” rich in agriculture and pastures. This name took on new resonance after 2011, as government forces retrenched from the region. Kurdish-led militants used the chance to pursue their long held dream of autonomy—benefiting, in the process, from ready access to energy, water, and aid flows entering from neighboring Iraqi Kurdistan. Consolidation of Kurdish control triggered conflict with neighboring Türkiye, which occupied an area from the Turkish border to the strategically vital M4 motorway. As Syria’s transition unfolds, the region’s fate is among the country’s most urgent question marks.

3. Energy flows

As Syria fractured, northeastern oil kept flowing west to cities and infra-structure. For decades prior, oil structured the region’s ties to Damascus: a colonial-style relationship in which the capital dispatched civil servants to oversee extraction of oil, which was then piped to refineries and power plants in the west. The northeast saw little benefit, whether in terms of jobs or infrastructure. This connection persisted throughout the conflict: The Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), like the Islamic State (ISIS) before them, relied on revenues from smuggling oil products across the Euphrates via a makeshift network of trucks and boats.

4. Blank space

A final structuring feature is the presence of vast swathes of the country that are mostly uninhabited—primarily in the central desert, but also parts of the northeast. That’s not to say they are empty: the central desert is home to most of Syria’s natural gas reserves; the roads linking the provincial capital of Deir Ezzor to cities in the west; and residual pockets of ISIS insurgency, which threaten everyone from security forces to truffle hunters.

Zooming in: Connectors and dividers

A closer look at the map reveals trends that help explain local sources of conflict, but also enduring sources of connection and diversity.

Demographic mixing

Syria’s

conflict was not without intercommunal violence, self-segregation, and

even ethnic cleansing. But unlike neighboring Lebanon—whose civil war

prompted a major reordering of society into homogenous enclaves—much of

Syria retained its ethnic, religious, and social diversity. Such areas

now face unresolved tensions and the potential for retaliation. But

they also offer opportunities to build on the diversity that has long

made Syria what it is.

- The

rural influx

Starting in the 1960s, Syria’s three largest cities—Aleppo, Damascus, and Homs—were transformed by waves of migration from

the countryside. This shaped the geography of Syria’s uprising: Fed up

with poor services and the classism of urban elites, rural migrants

disproportionately took to the streets, first as protesters, then as

rebels. This deepened longstanding class divisions, as elites often

blamed the poor for instigating the conflict.

- Communally

mixed cities

Urban-rural splits intersect with differences in sect and

ethnicity. In Qamishli and Aleppo, Kurdish communities mingle with

Syria’s Arab majority. In Damascus, Homs, Latakia, and Tartous, Sunni

and Christian areas abut Alawi ones. The latter took shape in the late

20th century, as rural Alawis sought jobs in an expanding state and

security apparatus. Intercommunal divisions deepened post-2011,

sometimes leading to intimate violence between neighbors. Many were

nonetheless forced to find ways of living together, in cities whose

urban fabric makes self-segregation impossible.

- Communally

mixed countryside

Some of Syria’s worst intercommunal violence

occurred in rural areas dotted with a mix of Sunni and Alawi

villages—including in the hinterlands of Damascus, Homs, Hama, Latakia,

and Tartous. In areas emptied of residents, tensions were amplified by

the fact that some communities could return while others could not;

worse still, homes and farmland have in places been expropriated.

Meanwhile, Kurdish communities in northwest Syria witnessed extreme

violence and dispossession at the hands of Türkiye and its Syrian

allies. Among other problems, such violence sowed chaos around housing,

land, and property rights.

Connective infrastructure

Even at the height of Syria’s fragmentation, the country’s disparate parts remained bound by physical and administrative infrastructure. On one side, this helped preserve social and economic ties across conflict lines. On the other, warring parties leveraged control over infrastructure to strengthen their position and punish their rivals. Today, a key question concerns how this infrastructure can be revitalized to the benefit of all Syrians.

- Administrative hubs

Throughout the war, communities outside government control crossed conflict lines to carry out bureaucratic tasks: from registering births, deaths, and marriages to sitting for public school exams. These hubs, which shifted during the conflict, anchored peripheral regions to Syria’s center. Citizens could keep essential documents up to date, while Damascus projected a form of authority into areas outside its control. But this did not serve every one. Young men wanted for conscription or detention steered clear of such facilities. Others—including single women—struggled to make long, dangerous, and expensive journeys. Today, there is an urgent need to support countless Syrians left without proper civil documents, educational degrees, and property deeds.

- Energy

Syria’s energy sector was hit hard by war: Fuel prices rocketed, power stations were bombed or looted, and state electricity collapsed. While a privileged few kept the lights on 24/7, vulnerable Syrians were left in the dark. Faced with extreme scarcity, Syria’s disparate regions continued to rely on old energy flows. Trucks moved crude oil from Hasakeh in the northeast to the refinery in Baniyas, on the western coast. The SDF-controlled Tabqa Dam provided electricity and irrigation water across conflict lines, with help from Syrian government engineers who stayed on the job throughout the war.

- Transport infrastructure

High fuel prices, checkpoint-based extortion, and territorial fragmentation have for years constrained the movement of goods and people across Syria. But mobility never stopped: Manufactured goods passed through Turkish-controlled Syria into government-held Aleppo; agricultural inputs and products made their way from Daraa up to Raqqa, or from Hasakeh to the port of Latakia. Syrians crisscrossed the country to visit family, check on property, or carry out administrative tasks. This often meant bribing armed groups, thus rewarding the very actors that made movement prohibitively costly for many. The coming phase poses the challenge—and the opportunity—of reviving these linkages, both within Syria and with its neighbors.

Environmental anchors

- Key rivers

The Euphrates and Orontes are among Syria’s most precious resources. They nourish its farms, sustain population centers, and—in the case of the Euphrates—provide much-needed hydro electric power. In recent years, however, both have been degraded by a mix of neglect and competition: poisoned by unregulated industry and fuel smuggling, depleted by communities racing to pump their share as river levels fall. Conserving, managing, and rehabilitating these resources may serve as an arena for cooperation between disparate communities.

- Agriculture

Agriculture has long anchored ties between Syria’s urban centers and its rural hinterlands. Conflict strained those con nections, as farmers and pastoralists struggled to move produce and livestock to urban markets separated by long distances and costly, dangerous checkpoints. Many traders and producers none theless managed to continue, preserving links that will prove es sential if Syria is to regain its ability to feed itself. Indeed, its growing reliance on imports threatens the hard currency it needs to stabilize the economy.

Download map as a two-page PDF or poster.

May 2025

Text by Alex Simon, map by Monica Basbous